“Our owner, Chris Weld, reached out to Sam Adams about doing a collaboration project—he wanted to combine the worlds of craft whiskey and craft beer. Chris and Sam Adams’ Jim Koch put together the details, and eventually we distilled Boston Lager as well as a bock-style beer.

“The process was similar to what we do here [with] everything in the distillery—we taste every barrel of the product every six months to a year. We aged these for four years and then ended up releasing them a little bit after.

“The project was great. It piqued the interest of a lot of craft-beer drinkers and a lot of people who aren’t too familiar with distilling as a whole. We got the common question of, ‘Oh, I didn’t know you could distill beer?’ Beer is fermented grain, and then whiskey is distilled grain. So, it’s kind of a one-two step.”

Building on that Success

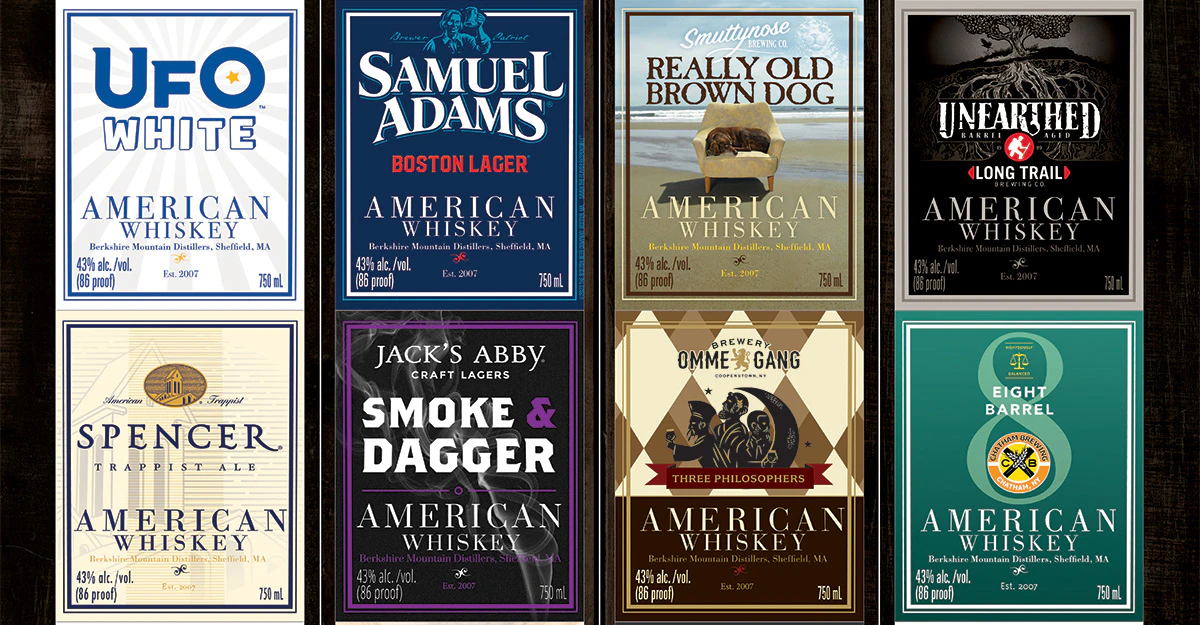

“We thought, oh, this could actually be something. We drummed up this idea where we could expand the program and [came up with the idea] for the Craft Brewers Whiskey Project. The idea was to take 12 different beers from 12 different breweries—all eclectic breweries from around the Northeast—and then distill those beers.

“Sam Adams was the anchor for the whole project—they give a lot of validity to the work that’s being done. We probably tried three or four different styles of beer from each brewery, then selected the ones that we thought had the best flavor profile as well as ones that were going to be a bit more unique for the brewer as well.”

Process and Adjustments

“We run two pot stills—one is an 850-gallon stripping pot, and then we have an 825-gallon spirits pot. Both are steam-fed.

“We tend to run our distillations a bit slower; it just allows a little bit more formation of flavor, hoping not to scorch anything as it’s going through. Distilling beer isn’t a lot different from our whiskey-distillation process.

“We make sure the still is very clean before we put anything else into it. The hop oils and resins, through the heating process, tend to form together a little bit more. They can create a sticky material on the inside of the still as it’s cooking. We do a hot caustic clean every time we use the still; we steam everything through, as well. So, everything gets scrubbed down pretty hard and then steamed out for final approval. That goes for every time we run the still because we’re also making gin, we’re doing rum. Having a really sterile workspace each time you distill is key.

“We did work with the brewers on some of the flavor profiles that we were looking for. We had some of the breweries lower the level of hops in the beer because those can give off some pretty heavy resin and bitter flavors in the finishing notes after the distillation.

“We also asked them to brew [some of the beers] at a higher level of alcohol, while keeping the flavor profile the same. Sam Adams brewed Boston Lager closer to 7 percent ABV. We really want the flavor of the beer we’re distilling and the product to be as close as possible to what the consumer is drinking out of the bottle or on tap. That way, as we distill it, we’re still able to get the same flavor profiles.

“Most of the spirits came out of the barrel at five years, and we’ve had some of it come out at six. We still have some barrels that we’re just kind of waiting to see what happens around the eight-year mark. The longest one so far has been an Oktoberfest with Berkshire Brewing—that was actually 12 years in the barrel.

“What we’re seeing is that [with] the really heavy, dark-malt beer profiles, we want to let [those] sit a bit longer because it allows us to extract more of the wood sugars from the barrel. It becomes more of this chewy mouthfeel, which is very reminiscent of dark chocolate and almost-toffee flavors that tend to go well with that style of beer.

“The lighter beers, like some Belgians and the pale ales, can use a little bit less time in the barrel. Even with those, however, we found that at year five or six, the bright orange flavor that you typically have in those beers has now turned into a really cool, burnt-orange-like flavor, and it’s almost like a savory flavor.”

The Results

“You can actually taste all of the beer styles in the final product. Saison, stout, brown ale, Oktoberfest—the flavors translate really well.

“The beers that we did that were more yeast-flavored, like the saison and the Belgian styles more broadly, I found citrus and light floral flavors coming though in the center of the spirit profile. With the UFO White [brewed by Harpoon], I get more peppercorn and a very light spice as an accent on the finish. For Brewery Ommegang’s Three Philosophers, which is a Belgian quadrupel style, I get a lot of dark cherry, almost a burnt-orange-peel flavor. These are very reminiscent of the flavors of the beers themselves.

“The beers that I probably prefer most [to distill] are the ones with darker malt tones—they tend to be better. Like with that Three Philosophers beer, you’re getting a deeper, richer malt flavor out of the beer. We did a stout with Long Trail and a smoked black lager with Jack’s Abby. When you use the deeper, darker malts, and even chocolate malts, you start to get this dark chocolate, almost sweet-coffee flavor that gets developed in the raw distillate itself. This is before aging, before any other processing, you get these rich, deeper malt flavors that I find very interesting.

“We do straight oak-barrel aging on these, mostly because we don’t want to dilute the natural flavor. We’ve done other finishes on our standard product line, but with the distilled beers, the flavors are so unique to the beer itself, we don’t want to cover it up with more fruit notes from something like a port barrel, or peppery notes from other barrel types. We just want to keep the base product very clean and clear with what it is.

“For a [pale] lager style, it’s pretty base-forward. It comes out more like an Irish whiskey. A lot of the time, you’re using malted barley, or a 100 percent barley base, and the lagers tend to come out similar to that.

“One thing that didn’t work was juicy IPAs. When we started this project, breweries were really getting into these beers, especially here in the New England area. We tried distilling a couple of them on test runs, but flavor-wise, it was not something that we were [happy with].

“We use these [beer spirits] in cocktails—they make very interesting cocktail combinations. They stay on par with other whiskeys out there and dive into some of the more interesting things you don’t typically get in the standard whiskeys.”

Market and Future Outlook

“The focus of these whiskies is beer fans. They turn into collector’s items at some point in time. We’ve also started seeing more macro-breweries start distilleries over the last few years. You get a lot of loyalty behind the brand itself. That’s also why we chose a lot of these places with big names that we can partner with.

“In our tasting room, here at the distillery, we get a lot of people coming in that have never heard of [the project], never seen distilled spirits made with beer. It’s very exciting for them to then taste a few things and wrap their head around the process. They find it really interesting.

“We distribute throughout New England and New York. One of the great things about the project is that we sold the spirits in surrounding states, in the home states of each brewery. So, Brewery Ommegang from Cooperstown was sold across New York state. Two Roads in Connecticut, they got a lot of their products sold in their state. We want to get the product in the hands of fans of the brewery. The breweries have been a great source of promotion.

“We’ve done 15 different beers so far, and we have other partners that we’ve been working with continuously since those have been released. We’re looking at five to eight new beer selections that will be released over the next couple of years. We’re dealing with some new breweries this time around, trying out new beer styles, and it’s just a great way to garner a second group of fans here at Berkshire Mountain—fans who are now following the Craft Brewers Whiskey Project.

“We’re always being asked about when the next one is coming out—‘When are we going to see the next beers?’ ‘Who are you working with?’ Dealing with things in the distillery world, you can’t rush time in a barrel, so we try not to get overly excited about some of the stuff we have aging. Once they’re ready, we’ll hit the ground running.”