arrack, Batavia , a pungent, intensely flavorful sugar cane–rice spirit from Indonesia, has been traded internationally and even intercontinentally since the 1600s, making it one of the oldest spirits in global commerce. It is also the first and, so far, only Asian spirit to gain broad acceptance in the West (although that acceptance peaked in the eighteenth century). Perhaps that is because of its cosmopolitan origin: created by overseas Chinese distillers applying their native techniques to Indonesian ingredients and financed by Dutch capital, Batavia arrack (it takes its name from Batavia, the Dutch colony that evolved into the modern Jakarta) is as much a product of the colonial age as its relative rum.

We do not know the precise circumstances of the spirit’s creation. It is not mentioned by Ibn Battuta, who visited Java in the 1300s, or by Fernão Mendes Pinto or any of the other Portuguese who recorded their experiences on the island in the 1500s. It was only during that century, however, that significant numbers of Chinese settled in Java, working as artisans, merchants, and farmers. Among the trades the Chinese brought was distilling. They used a compound base for their spirit, adding palm wine to the rice used for distilling in southern China. In the early 1600s, when the Dutch financed a Chinese-managed sugar industry on the island, the distillers began adding the molasses and other byproducts thrown off by the sugar-making, possibly at Dutch instigation. See also lambanog.

A handful of detailed accounts of the spirit’s production from the early nineteenth century give some insight into the hybrid nature of the resulting process, although it is unknown how closely they tally with the original sixteenth-century manufacture. First, glutinous rice is piled in a heap and moistened with water that has been mixed with molasses, and yeast is added (presumably in the form of jiuqu) for a dry fermentation in the Chinese style. Separately, more molasses is combined with palm sap and water, for a liquid Western-style fermentation (it should be noted that the Chinese in Java had been making sugar from mixed sugar cane juice and palm sap since at least the 1500s). Proportions varied, but four parts molasses to two parts rice and at the very most one part palm sap is common.

The liquid thrown off by the rice is combined with the molasses-palm mix for further fermentation and then distillation in Chinese-style egg-shaped stills modified by European condensing coils. The low wines are then usually redistilled twice or thrice (like most Chinese spirits and unlike most South Asian arracks, Indonesian arrack is quite strong, at over 50 percent ABV) and the distillate placed in teak-wood vats for aging or wooden casks for shipping.

Batavia was the capital of the arrack trade, but considerable production was also centered on Cirebon in West Java and Surabaya in East Java. In both of those regions, however, the molasses used came from large, Dutch-run sugar plantations, while the distillers in Batavia bought theirs from smaller, family-run plantations. The latter, due to less efficient processing, had more residual sugar and produced a higher-quality spirit.

By the end of the seventeenth century, Batavia arrack was being shipped to Europe in considerable quantities, mostly by the Dutch, who had control of the island of Java, but also by the English. From the Netherlands, it went on to Scandinavia and Germany, while the English re-exported it to their American colonies. The spirit enjoyed an enviable reputation for quality. Indeed, in London, the world’s greatest spirits marketplace, Batavia arrack sold in punch houses for eight shillings a quart, while the finest French brandy cost only six. The spirit’s primacy endured in Britain through the eighteenth century and well into the nineteenth. Although its dry tang was not appreciated by all, arrack was nonetheless the punch connoisseur’s choice (see Regent’s Punch). Meanwhile, in northern Europe, arrack was commonly drunk in tea or coffee, and Arrack Punch was so well established as to become a pillar of local drinking customs (indeed it is still sold in bottled form, as Swedish Punch). In America, arrack’s deep pungency made it challenging to incorporate in the standard spectrum of American cocktails, Juleps, and the like. Indeed, “it is but little used … except to flavor punch,” wrote Jerry Thomas in 1862, although it “is very agreeable in this mixture.”

Over the course of the nineteenth century the arrack trade, by then entirely in Dutch hands, saw a good deal of streamlining and consolidation. At some point, palm sap fell out of the formula. In 1899, the main distilleries, KWT and OGL (the names represent the initials of their Chinese founders), were consolidated under the umbrella of the Batavia-Arak Maatschappij, or BAM, the leading purveyor of the spirit until World War II. After that war, which entailed years of German occupation of the Netherlands and Japanese occupation of Indonesia, the industry emerged much smaller than before, although Batavia arrack still had and has significant uses in the confectionery and tobacco industries. Some arrack is still also drunk, mostly in Scandinavia and Germany, either straight, premixed into punch, or “verschnitt”—cut with neutral spirits. All of these markets are supplied by a handful of now Indonesian-run distilleries in Java, all of which export through E. & A. Scheer, the heir to BAM and indeed the entirety of the arrack trade.

Batavia arrack is also one of the “lost” ingredients to benefit from the cocktail renaissance, with it returning to the American market in 2008 after a hiatus of at least fifty years. It is seen as a rewarding challenge among bartenders to feature its burly funkiness in cocktails and tiki drinks, usually as an accent rather than a main ingredient. The spirit also features in some rum blends, where a touch of it adds desirable complexity and aromatics.

Campbell, Donald M. Java: Past and Present. London: Heinemann, 1915.

Raffles, Thomas Stamford. The History of Java, vol. 1. London: Black, Parbury & Allen, 1817.

Scott, Edmund. An Exact Discourse of the Subtilties, Fashions, Pollicies, Religion, and Ceremonies of the East Indians. London: 1606.

Verhoog, Jeroen. Walking on Gold: The History of Trading Company E & A Scheer. Amsterdam: E & A Scheer, 2013.

Wondrich, David. Punch. New York: Perigee, 2010.

By: David Wondrich and Jacob Grier

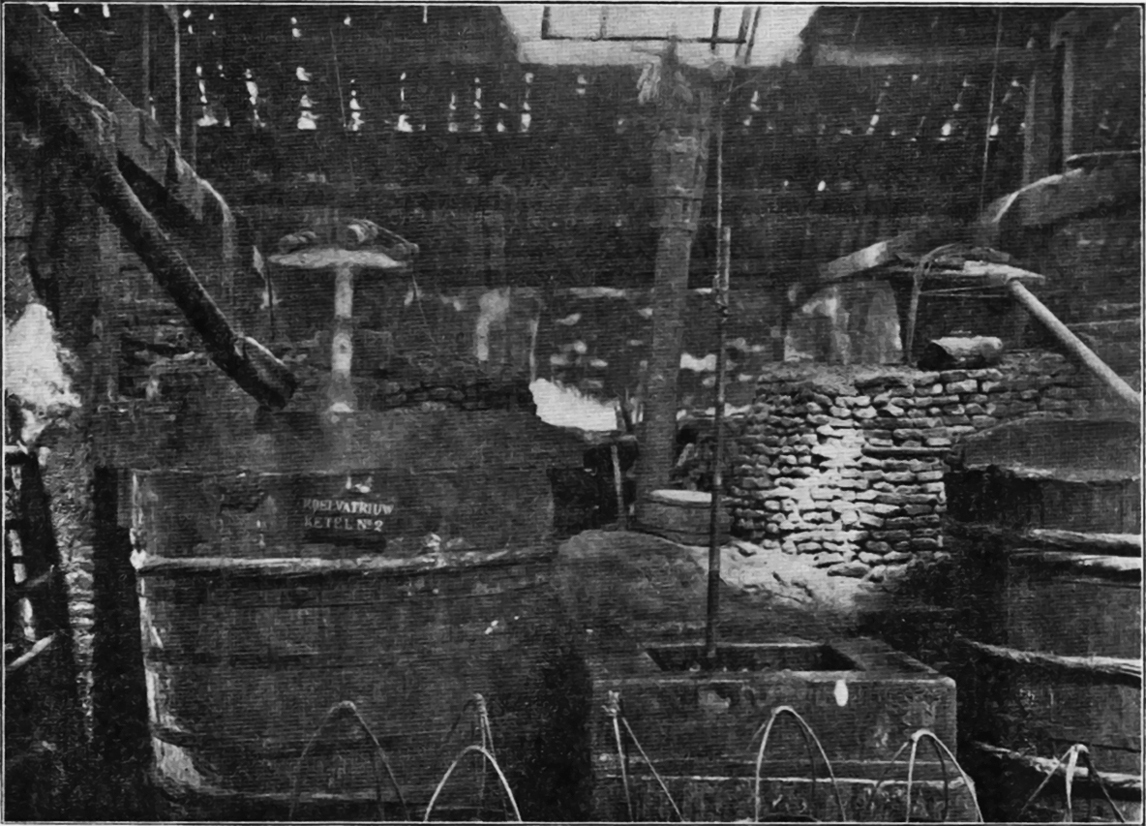

This very rare, murky picture shows the still room at the OGL or KWT arrack distillery in Jakarta. The bollard-shaped heads of the Dutch-style pot stills can just be made out at center right and center left, with sticks used to tension the wires holding them onto the still.

Wondrich Collection.

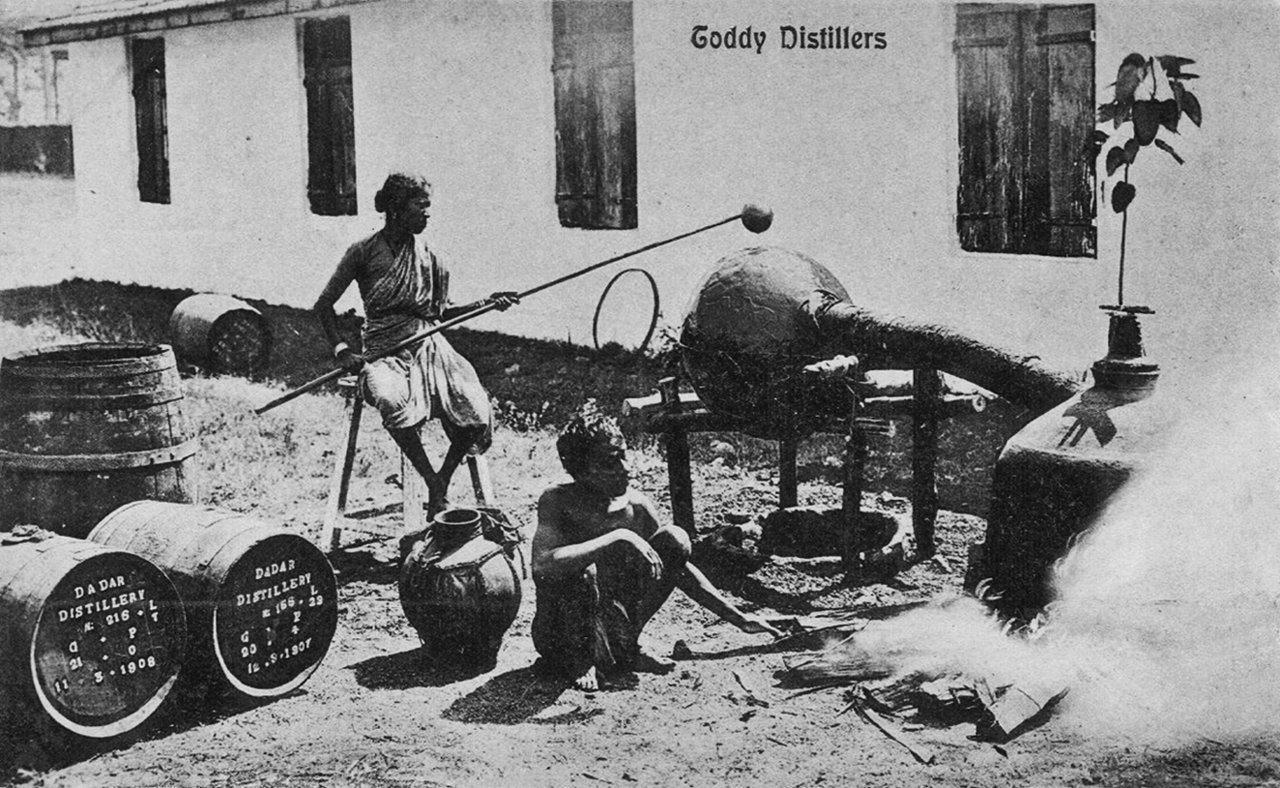

Distilling tadi (palm wine) into coconut arrack at the Dadar Central Distillery, Mumbai, 1908. Note the modified Gandharan-style still, with the pot at the right and the receiver sitting in its bowl of cooling water at center, with more being ladled on top from the reservoir beneath.

Wondrich Collection.

This very rare, murky picture shows the still room at the OGL or KWT arrack distillery in Jakarta. The bollard-shaped heads of the Dutch-style pot stills can just be made out at center right and center left, with sticks used to tension the wires holding them onto the still. Source: Wondrich Collection.

This very rare, murky picture shows the still room at the OGL or KWT arrack distillery in Jakarta. The bollard-shaped heads of the Dutch-style pot stills can just be made out at center right and center left, with sticks used to tension the wires holding them onto the still. Source: Wondrich Collection.

Distilling tadi (palm wine) into coconut arrack at the Dadar Central Distillery, Mumbai, 1908. Note the modified Gandharan-style still, with the pot at the right and the receiver sitting in its bowl of cooling water at center, with more being ladled on top from the reservoir beneath. Source: Wondrich Collection.

Distilling tadi (palm wine) into coconut arrack at the Dadar Central Distillery, Mumbai, 1908. Note the modified Gandharan-style still, with the pot at the right and the receiver sitting in its bowl of cooling water at center, with more being ladled on top from the reservoir beneath. Source: Wondrich Collection.