okolehao is a Hawaiian spirit made from the native ti (or ki) plant, Cordyline fruticosa, and bottled at 40–65 percent ABV. Also known as “Hawaiian moonshine” or simply “oke,” it was introduced to the islands in the 1790s by William Stevenson, an Australian fugitive. Traditionally, Hawaiians had roasted the large, tuberous ti stems underground for several days, as is done with agave piñas in Mexico (the plant, whose “roots” weigh some 15–20 kg, is a relative of the agave); this would convert their starches to sugars, from which they brewed a mild, beer-like intoxicant. Stevenson taught distillation, jury-rigging a still from two discarded whaling ship blubber-boiling pots, with a gun barrel to draw off the spirit. The repurposed twin cauldrons resembled human buttocks, hence the spirit’s name: okole is Hawaiian for “buttocks” or “bottom” and hao for “iron.”

The natives called oke a “gift from heaven,” but Yankee missionaries denounced the ti as “the tree of sin” when they pushed for prohibition of all alcohol upon their 1819 arrival. Periodic government bans dogged oke production into the mid-twentieth century, with island bootleggers—who adulterated their ti mash with rice, taro, or any other cheap fermentable starch at hand—routinely jailed for operating oke stills.

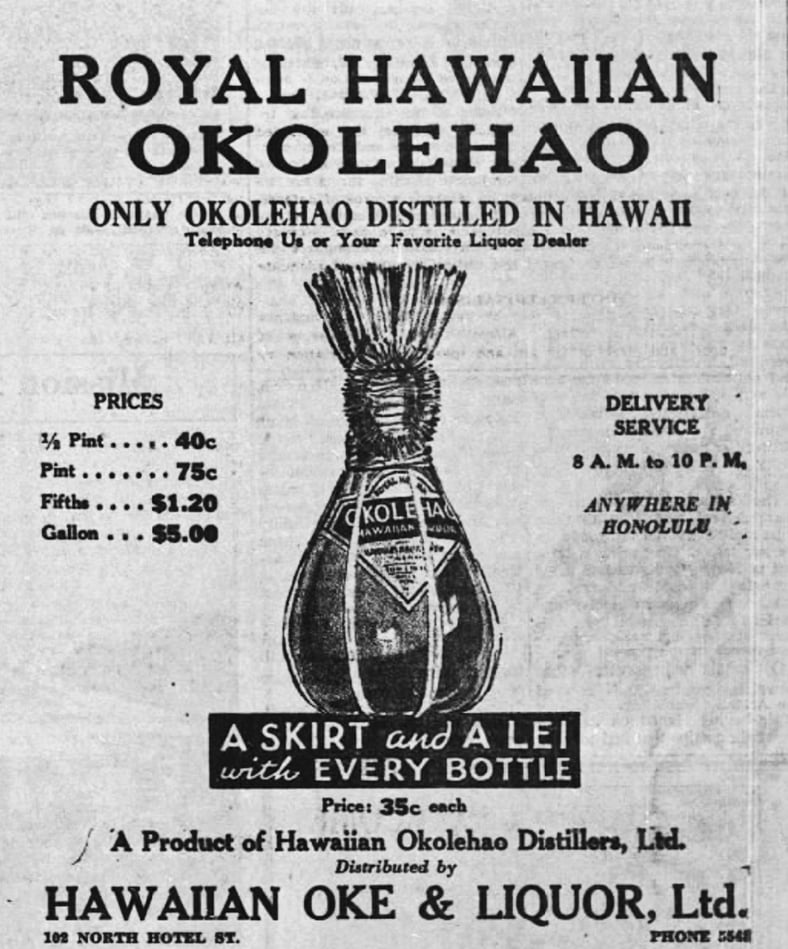

The first attempt at making legal okolehao was in 1907, when entrepreneurs set up the Kona Okolehao Distillery on a ti plantation at Ke’ei, near Kona on the Island of Hawaii, using a batch (i.e., pot or three-chamber) still with a doubler and aging the resulting spirit in charred oak barrels in the American style. See still, three-chamber. Although the spirit was well received, it struggled to find a market, and the distillery closed well before Prohibition set in. In 1935, after Repeal, two new brands were launched, the oak-aged Royal Hawaiian and Old Ti Root. The former, however, appears to have been made from “corn, cane sugar, malted barley, and malted rice,” while the latter may have been redistilled from imported spirit. Both companies were bankrupt by the end of 1940.

The jet-age Hawaiian tourism boom reversed oke’s fortunes as visitors created a demand for authentic local products. In the 1960s Hawaiian Distillers, a Honolulu-based company, bottled the spirit in tourist-friendly ceramic souvenir decanters in the shape of King Kamehameha I—ironically, the first government official to ban oke.

Hawaiian Distillers’ ersatz okolehao—it was actually Kentucky bourbon infused with ti extract—disappeared in the late 1970s. Only since 2012 have local Hawaiian distilleries begun producing oke again, this time from actual ti root augmented with sugar cane.

Alexander, William De Witt. A Brief History of the Hawaiian People. New York: American Book Co., 1891.

Berry, Jeff. Beachbum Berry’s Sippin’ Safari. San Jose, CA: Club Tiki, 2007.

Hoover, Will. “Will New ‘Okolehao be Your Cup of Ti?” Honolulu Advertiser, June 1, 2003.

Rowley, Matthew. “Okolehao, Historic and Modern.” Rowley’s Whiskey Forge, January 17, 2014. http://matthew-rowley.blogspot.com/2014/01/okolehao-historic-and-modern.html (accessed April 23, 2021).

“Royal Hawaiian Okolehao” (advertisement). Honolulu Advertiser, March 22, 1935, 9.

By: Jeff Berry

“A skirt and a lei with every bottle.” Advertisement for Royal Hawaiian Okolehao, 1935. Source: Wondrich Collection.

“A skirt and a lei with every bottle.” Advertisement for Royal Hawaiian Okolehao, 1935. Source: Wondrich Collection.