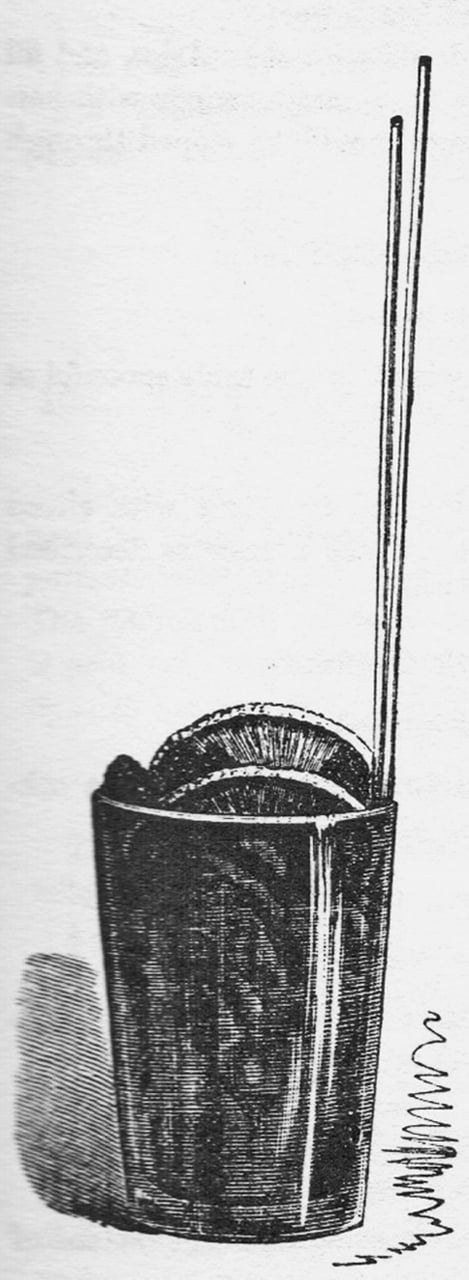

The cobbler is a nineteenth-century American drink consisting of wine (or sometimes a spirit) shaken or tossed with sugar, ice, and citrus peel or slices and elaborately garnished with berries and slices of fruit. Along with the cocktail and the julep, it was one of the cornerstones of American drinking and did more than any other to spread the gospel of iced drinks mixed to order around the world. See cocktail and julep. It was also the drink that did more than any other to popularize the use of the straw, through which it was invariably drunk.

The first record we have of the drink is from 1837, when a New York newspaper mentions a “Madeira Cobler [sic],” with the implication that it is something new. The Sherry Cobbler turns up the next year, but by 1839 is so popular in New York and beyond that one suspects that it had already been circulating for a while. See Sherry Cobbler. It would go on to be the cobbler’s most popular manifestation by far, consumed anywhere the weather was warm and there was ice to be had (the Madeira Cobbler, on the other hand, sank without a trace).

The origin of the cobbler is obscure and its creator unknown. It has been posited that it was an American adaptation of Cobbler’s Punch, a British drink of the early nineteenth century, but there is no evidence that the latter drink was known in America, and there is little commonality between the beverages. See

In the early 1840s, the popularity of the Sherry Cobbler inspired a raft of other variations, most based on wine or fortified wine. In 1843, however, Peter Brigham added arrack and brandy versions to the famous 1843 list of drinks served at his Boston saloon. See Brigham, Peter. The latter of those took on a certain popularity, particularly in Europe, while in America the Whisky Cobbler had its adherents. These spirituous versions, however, rather militated against the drink’s strong point, which was as a lighter, less intoxicating alternative to its hot-weather companion, the mighty julep. There were also those who wanted the drink lighter still, and Claret, Hock, Catawba, and even Champagne Cobblers had their vogue in the years after the American Civil War. The occasional specialized version appears, including the Pineapple Cobbler (1851) and the Cranston Cobbler (with champagne and “a cordial”; 1861), but by and large cobblers were simple drinks, with little elaboration (although Harry Johnson did like to make his with flavored syrups instead of plain sugar, and a float of port wine was sometimes also deployed). See Johnson, Harry, and float. In the last decade of the nineteenth century, the Cobbler saw itself largely supplanted by other, newer iced drinks, such as the rickey, the highball, and various coolers. See rickey; Highball; and cooler (inc. breezes). By Prohibition, in 1919, it was a musty antique: something one would find in the pages of a bartender’s guide but not in an actual bar. The cocktail renaissance has reawakened interest in it, to a degree, with bartenders spinning variations on the basic formula, although none has displayed any signs of becoming part of the canon. See cocktail renaissance. Bellocq, the elegant New Orleans bar devoted to the cobbler that opened in 2012 was forced to broaden its focus in short order.

“Burton-the late William H.-invented Sherry Cobblers.” Washington Evening Star, March 24, 1860, 1.

“The Weather.” New York Morning Herald, August, 9, 1837, 1.

Thomas, Jerry. How to Mix Drinks. New York: Dick & Fitzgerald, 1862.

By: David Wondrich

Jerry Thomas’s Sherry Cobbler (probably drawn by himself), 1862. Source: Wondrich Collection.

Jerry Thomas’s Sherry Cobbler (probably drawn by himself), 1862. Source: Wondrich Collection.