malting , in which grain is allowed to germinate (thus releasing enzymes that convert its starches to sugars) and then heated to stop further growth, is an essential part of the brewing and distilling process. The saccharification of the grain’s starches allows fermentation to occur when the malt is combined with water and yeast. See fermentation and saccharification. Malt, the result of the malting process, is most commonly produced from barley. However, malt is also made from oats, rye, wheat, and maize. For the purpose of this discussion, the malting of barley serves as the primary focus.

Since the mid-twentieth century, the greatest portion of grain that is turned into malt is purchased and accepted for processing between August and September. Bulk storage requires the grain to be “sweated,” or dried from an initial moisture content of about 19 percent to approximately 12 percent before it can be stored after it is carefully selected; cleaned of dust, dirt, awns (the spikes or bristles that grow from the seed head), and other undesirable elements; and graded. Newly harvested grain is inspected to confirm the bran is soft to the touch and that there is ample starchy endosperm to nourish the kernel’s germ. Henry Stopes, in 1885, itemized the flaws that disqualified grain from selection: any crop that is more than three years old; grain showing signs of mold, insect, or vermin infestation; and a crop with visible damage from reaping, threshing, hummeling, dressing, or stacking.

Grain that meets these quality assurances is then tested to ensure the germ is alive and therefore viable. One old method involved placing a few kernels on a red-hot cinder. If the kernels danced around, they were assumed to be alive. Those that burnt on impact were of no value. Another test involved slowly dropping kernels into a tumbler of water. Kernels that quickly and steadily dropped to the bottom and lay flat were viable. Those that floated or stood up upon descent were unhealthy. Yet another test involved soaking one or two hundred kernels for twenty-four hours in a piece of flannel laying on a plate. The sample was then drained and allowed to sprout for thirty-six to fifty hours at a temperature above 13° C (56° F). By the nineteenth century, a handful of patented devices sped up this testing stage, an improvement over the concurrent acid test that involved splitting a kernel lengthwise and applying a drop of concentrated, pure sulfuric acid. If after a few minutes the kernel core turned black or brown, the grain was considered to be useless. Grain that passed any such tests is then sweated before it is stored for about six weeks to avert dormancy of the live kernel, an environmental adaptation found in most cereal grain.

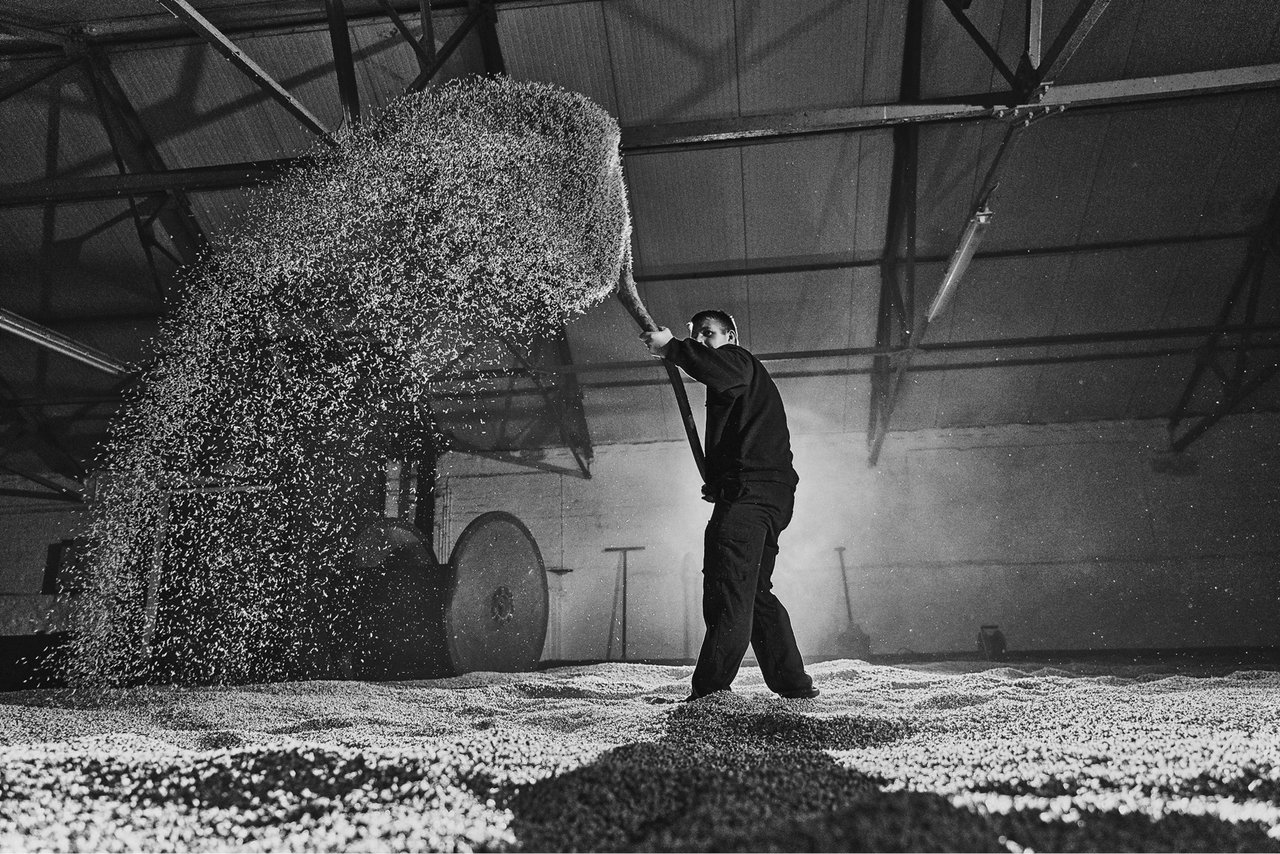

floor malting. Modern, large-scale malting operations employ a mechanical turning device to accomplish this same step. The “green malt” is then dried in an oven to terminate germination and encourage caramelization. In Scotland and parts of Ireland, it was traditional to use peat for the fuel and let the smoke rise through a perforated floor to surround the malt, but drying malt over (much less smoky) coke fires was in common practice as early as 1662. See peat. Cheaper than toasting over wood fire and less noxious than processing over coal, the resulting “malt” can range in color from pale to amber to dark chocolate with a moisture content of about 4 percent, depending upon the preferences of the individual distiller or brewer. The finished product is then ready to be milled and mashed with water to produce the wort that is combined with yeast to make beer and subsequently distilled spirits.Findlay, W. P. K. Modern Brewing Technology. London: Macmillan, 1971.

Hornsey, Ian S. A History of Beer and Brewing. Cambridge: RSC Paperbacks, 2003.

Macey, Alan. ‘New Method of Sweating Malting Barley in Bulk.’ Journal of the Institute of Brewing 58 (1952): 25.

Stopes, Henry. Malt and Malting. London: Lyon, 1885.

By: Anistatia R. Miller and Jared M. Brown

Turning the barley at the floor maltings in the Bowmore distillery, Islay, Scotland.

Courtesy of Beam-Suntory.

Turning the barley at the floor maltings in the Bowmore distillery, Islay, Scotland. Source: Courtesy of Beam-Suntory.

Turning the barley at the floor maltings in the Bowmore distillery, Islay, Scotland. Source: Courtesy of Beam-Suntory.