Thomas, Jeremiah P. “Jerry” (1830–1885), was a sailor, a gold miner, an artist, a theatrical promoter, and the most famous American bartender of his age. He was also the man who wrote the first bartender’s guide to document the unique American way of mixing drinks and, not coincidentally, the first American bartender to make it into the history books. His How to Mix Drinks, or the Bon-Vivant’s Companion, also known as the Bar-Tender’s Guide, has been cited as the authoritative early source on the topic ever since it appeared in 1862. Even in the dark days of the 1960s and 1970s his legacy never completely faded away, but it gained new currency with the cocktail renaissance of the twenty-first century, which looked to him and his work as one of its chief inspirations. See cocktail renaissance.

Thomas was born on October 30, 1830, in Sackets Harbor, New York, on the shores of Lake Ontario, but his family moved to the bustling port city of New Haven when he was still young. There, in the mid-1840s, he began working as a barback at the popular Park House hotel, managed by his older brother David. In 1847 or 1848, however, Thomas did what many young men of his generation were doing and shipped out as a sailor. How many voyages he served on and where they went are subject to conflicting information, but his last voyage, on the bark Ann Smith, is well documented: it left New Haven in March 1849, sailed around Cape Horn, and arrived in San Francisco in November. There, Thomas jumped ship and, as he later recalled, “ran off into the mountains after gold.” By the time he left California in 1851, he had $16,000 worth of the stuff in his pocket and had been a miner, bartender, theatrical promoter, and who knows what else beside.

It was while he was there, in June of 1862, that the New York publishing firm of Dick & Fitzgerald published the Bar-Tender’s Guide. The first book of its kind, it was widely reviewed and sales were high. Through it, Thomas did more than anyone else to establish a canon of American drinks. The drinks he included were distributed into classes, including cobblers, cocktails, fixes, juleps, punches, sours, slings, smashes, and toddies, plus a catchall category of “fancy drinks.” At the same time, however, Thomas excluded drinks explicitly associated with his contemporaries, some of them very popular, such as Peter Bent Brigham’s Moral Suasion or the Ladies’ Blush by Charles W. Geekie, of Baltimore. See Brigham, Peter Bent. Indeed, the only American bartender to whom Thomas credited any drinks is Joseph Santini of New Orleans, at whose Jewel of the South he might have worked during his time in that city. Of his own drinks, as far as can be established Thomas only included two: the Blue Blazer and the Japanese Cocktail. See Blue Blazer and Japanese Cocktail.

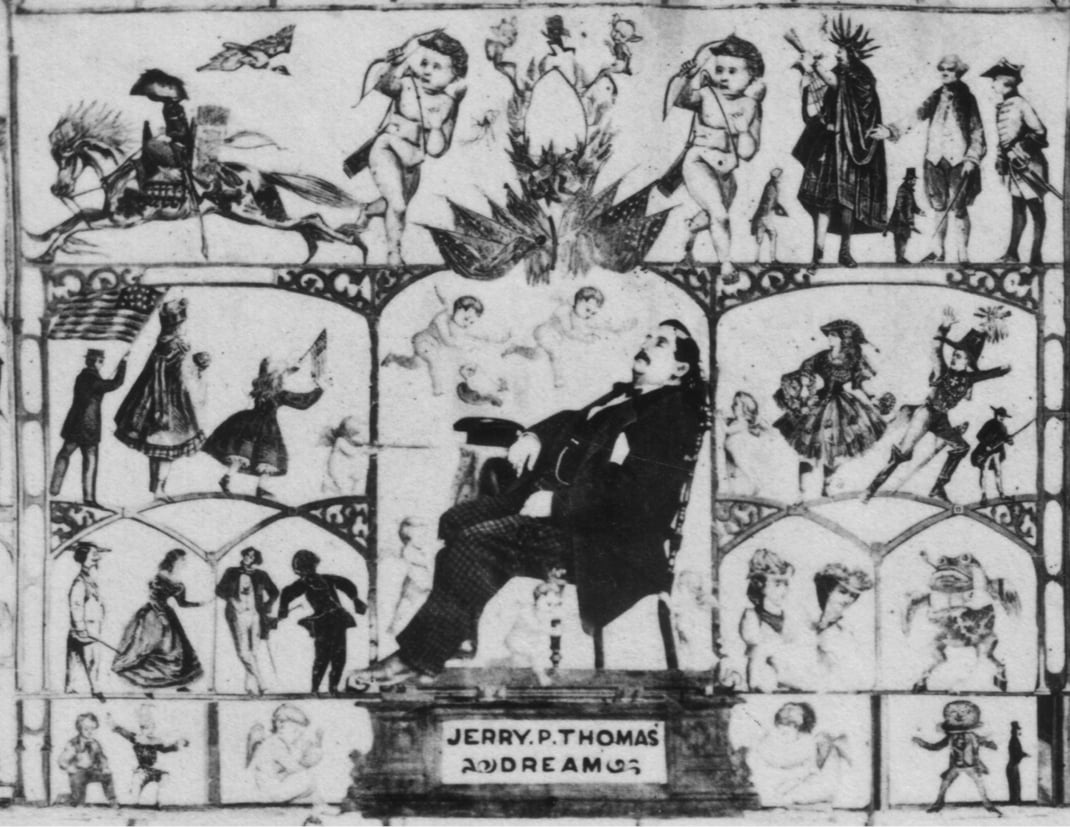

Thomas did not own the rights to the Bar-Tender’s Guide. At the end of 1863, at which point he had moved on first to the Occidental Hotel in San Francisco (under the same ownership as the Metropolitan) and then to the mining boomtown of Virginia City, Nevada, he self-published another book, The Portrait Gallery of Distinguished Bar-Keepers. Besides drink recipes, including many not in his previous work, the book contained biographical sketches of other American bartenders and a fairly extensive autobiography, along with illustrations by his own hand (among his many other talents he was a skilled artist). Unfortunately, no copies of this book are known to exist: all we have are a detailed review and a recipe book from 1867, The American Bar-Keeper, by the pseudonymous “Charles B. Campbell” of San Francisco, which pirated the recipes and some of the introduction. Were a copy to turn up, its biographies of Thomas’s colleagues would prove invaluable.

Thomas returned to New York and the Metropolitan in early 1865. The next year, he and George opened another Broadway bar, this one at Twenty-Second Street. This one proved to be one of the most popular in the city, known as much for its extensive collection of etchings as for the high quality of its drinks. In 1872, the brothers moved a few blocks further up Broadway, to a large space that proved even more popular than the last and cemented Thomas as a national figure—America’s bartender. That popularity was due in large part to the bar’s amusements: billiard tables, sports betting, bowling lanes, and even a basement shooting gallery. Add double life-sized portraits on the walls of Thomas mixing drinks and a statue near the entrance of the same, and you have the antithesis of the hushed modern speakeasy bar.

In 1876, Dick & Fitzgerald published a second edition of the Bar-Tender’s Guide, including an appendix of the latest drinks, among them the Collins, the Fizz, and the “Improved” Cocktail, the precursor to the Sazerac (there was also a posthumous third edition in 1887). See Collins; fizz; and Sazerac cocktail. By the end of the year, Thomas, who had invested improvidently in the stock market, had left the big bar on Broadway and moved downtown, across from the Astor House. From then on, his fortunes declined, and the string of bars he ran grew less and less ambitious, until he was reduced to working for others. He died on December 14, 1885, and is buried in Woodlawn Cemetery in New York. “Jerry Thomas was the best barkeeper I ever saw,” commented Charles Leland, his boss at the Metropolitan, after Thomas’s death. “He had no rival in the city.”

Yet by 1885, Thomas’s outsize, swaggering personality (he once gave an interview with a pair of white rats frolicking on his head and shoulders) was out of fashion among bartenders, with customers preferring the more deferential elegance of a William Schmidt. See Schmidt, William. Nonetheless, he remained the founding authority, the place one started when investigating the origin and development of American drinks, even when such things were of little interest to drinkers at large. Even as one macho-drinking San Francisco journalist commemorated the hundredth anniversary of Thomas’s book by pronouncing it a “frightening treatise” and asserting that the Professor (as Thomas had come to be known, after he was so dubbed by journalist Herbert Asbury in 1928) “knew nothing about the pleasures of alcohol,” others were publishing gin advertisements citing his authority (erroneously) for the origin of the Martini. See

In 1988, Joe Baum, the new operator of New York’s legendary Rainbow Room, instructed his head bartender, Dale DeGroff, to refer to Thomas’s book as he built the new bar program. See DeGroff, Dale. By then, the strong, elemental drinks Thomas collected came as a revelation, and their influence has permeated the cocktail renaissance—even if it has become fashionable in recent years among some mixologists to regard them as primitive artifacts whose only worth is the basis they provide for creative improvement.

“Jerry Thomas’s Career.” New York World, December 20, 1885, 23.

“Jerry Thomas’s Pictures.” New York Sun, March 28, 1882, 3.

Wondrich, David. Imbibe!, 2nd ed. New York: Perigee, 2015.

By: David Wondrich

Jerry Thomas’s Dream, detail, 1864. Thomas was an accomplished artist and this is his self-portrait. Source: Wondrich Collection.

Jerry Thomas’s Dream, detail, 1864. Thomas was an accomplished artist and this is his self-portrait. Source: Wondrich Collection.