punch , a mixture of spirits, citrus juice, sugar, and water, often with the addition of spices, is the foundational drink of modern mixology and the first mixed drink based on spirits to gain global popularity. Its descendants—including the Daiquiri, the Cosmopolitan, and the Margarita—remain at the peak of popularity today. And yet punch’s origins cannot be established with any precision or certainty.

The first mention of punch by name was found well over a century ago in the papers of the English East India Company, which was established in 1600, began trading with India the next year, and maintained trading posts there from 1614. In a 1632 letter, one of the company’s men at arms writes one to of its merchants who was in the small trading post of Petapoli on India’s southeast coast, about to sail up to Bengal as part of the company’s first trade mission to that rich province of the Mughal Empire. “I hop you will keep good house,” the soldier wrote, “and drincke punch by no allowanc.” Now, “by no allowanc” here can mean either “not at all” or “not limited by ration.” Either meaning suggests that the English found this “punch” strongly alluring. But what was it, and where did it come from?

The first question was answered in 1638, by Johan Albrecht de Mandelslo, a young German adventurer who found the British in Surat, on the Arabian Sea north of Mumbai, drinking “Palepuntz” (his phonetic rendering of “bowl o’ punch”), which he defined as “a kind of drink consisting of aqua vitae, rose-water, juice of citrons and sugar.” This is suspiciously like the English drink George Gascoine had detailed in 1576, “wine [with] … Sugar, Limons and sundry sortes of Spices … drowned therein,” with the water and the aqua vitae—in this case, local palm arrack—uniting to play the role of the wine. But it is even more like the drink that the English merchant Peter Mundy, who was in Surat from 1628 to 1630, noted was “sometimes used” by the English traders there. This was “a Composition of Racke [i.e., arrack], water, sugar, and Juice of Lymes.”

Mundy gives the name of this composition not as punch but as “Charebockhra,” which is a rendering of the Hindi chaar bakhra, or “four shares.” Mundy’s little-known passage dovetails with the a much better known one from another English traveler to India, John Fryer, who in 1676 wrote home about the “enervating Liquor called Paunch” he found the English drinking there. The name, he explained, was “Indostan for Five, from Five Ingredients” (the fifth ingredient was spices, whether Mandelslo’s rosewater or the more common nutmeg, mace, cloves, or cinnamon). See spices (for punch). Along with Mundy’s testimony, this strongly suggests that punch was an Indian drink. But unfortunately nothing yet has been found to corroborate that in Indian literature: we know of mixtures of citrus, sugar, and water and mixtures of spirits and water or spirits and wine, but not the full panoply. And “punch” is also an English word, used for something squat and round like the bowls in which punch was served (e.g., the gilded “paunche pot” recorded in an English will from 1600). It is an easy step from the “punch” in “punch bowl” describing its form to describing its function. Until further evidence turns up, the only thing we can say with certainty is that punch was a drink that the English made in India with local ingredients.

It was most assuredly the English who brought punch to the rest of the world, though. Early on, it was adopted by sailors, who could get the citrus at any port of call in the tropics or Mediterranean. The sugar and spirits would keep well even on the longest voyage, unlike beer or even wine, and they always had the water necessary for mixing it (if they didn’t, not being able to make punch was the least of their problems). By the 1660s, punch was the staple drink of the Caribbean and North America and had even colonized the British Isles, where it would quickly become the recreational drink of choice, and had begun seeping into the other countries of Europe and South America. The long century and a half between the 1670s and the 1840s was the great age of punch, when a shared bowl of punch of some sort—cold in the summer, hot or even flaming in the winter—was the drink of choice for an impressive chunk of the world. See

By the middle of the nineteenth century, a great deal had been learned about making punch even more seductive than it already was. Tricks such as the use of “oleo-saccharum” (the oil from citrus peels extracted into sugar) and a premixed “shrub” (citrus and sugar) for depth of flavor and efficiency, of milk or even calf’s-foot jelly for smoothness, of tea rather than water for spice, of still or sparkling (or even fortified) wine rather than water for potency (this was known as “Punch Royal”), and a dozen other little things turned a basic sailor’s drink into an epicurean one. See oleo-saccharum and shrub. But at the same time the ritual of gathering around the flowing bowl was increasingly out of step with modern life. It was too time consuming and ultimately too intoxicating to sit around and see off a bowl of punch with one’s companions, be they the Society of Steaks or the Ladies’ Punch Club (to name a pair of London institutions). Punch became a treat for special occasions, trotted out to impress or intoxicate, but not an everyday drink. See Chatham Artillery Punch.

As punch was made less and less often, that body of experience relating to its construction faded away and the drink became, for the most part, a slapdash assemblage of cheap ingredients geared to intoxicating the most people for the least money. Only in the 2010s did it get a serious second look, with books written about its history and mixologists—such as Nick Strangeway of London and Erick Castro of San Francisco—bringing it back, tricks and all, as an efficient way of getting a well-mixed drink into the hands of a crowd as quickly as possible. See cocktail renaissance and Strangeway, Nick.

See also England and India and Central Asia.

Recipe (Basic Brandy Punch): Peel 4 lemons in long spirals. Put the peels and 180 ml of sugar in a 1-liter jar, seal it, and let it sit overnight. To the resulting oleo-saccharum, add 180 ml strained lemon juice and shake until sugar has dissolved. Pour the contents of the jar, peels and all, into a 4-liter bowl over a 1-liter block of ice. Add 750 ml VSOP-grade cognac or Armagnac and 1 liter cold water. Stir well, grate nutmeg over the top, and ladle out in 90 ml servings. Makes 20+ servings.

Carnac, Richard, ed. The Travels of Peter Mundy in Europe and Asia, 1608–1667, vol. 2. Cambridge: Hakluyt Society, 1914.

[Cook, Richard]. Oxford Night-Caps. Oxford: 1827.

Turenne [pseud.]. La véritable manière de faire le Punch. Paris: 1866.

Wondrich, David. Punch: The Delights and Dangers of the Flowing Bowl. New York: Perigee, 2010.

By: David Wondrich

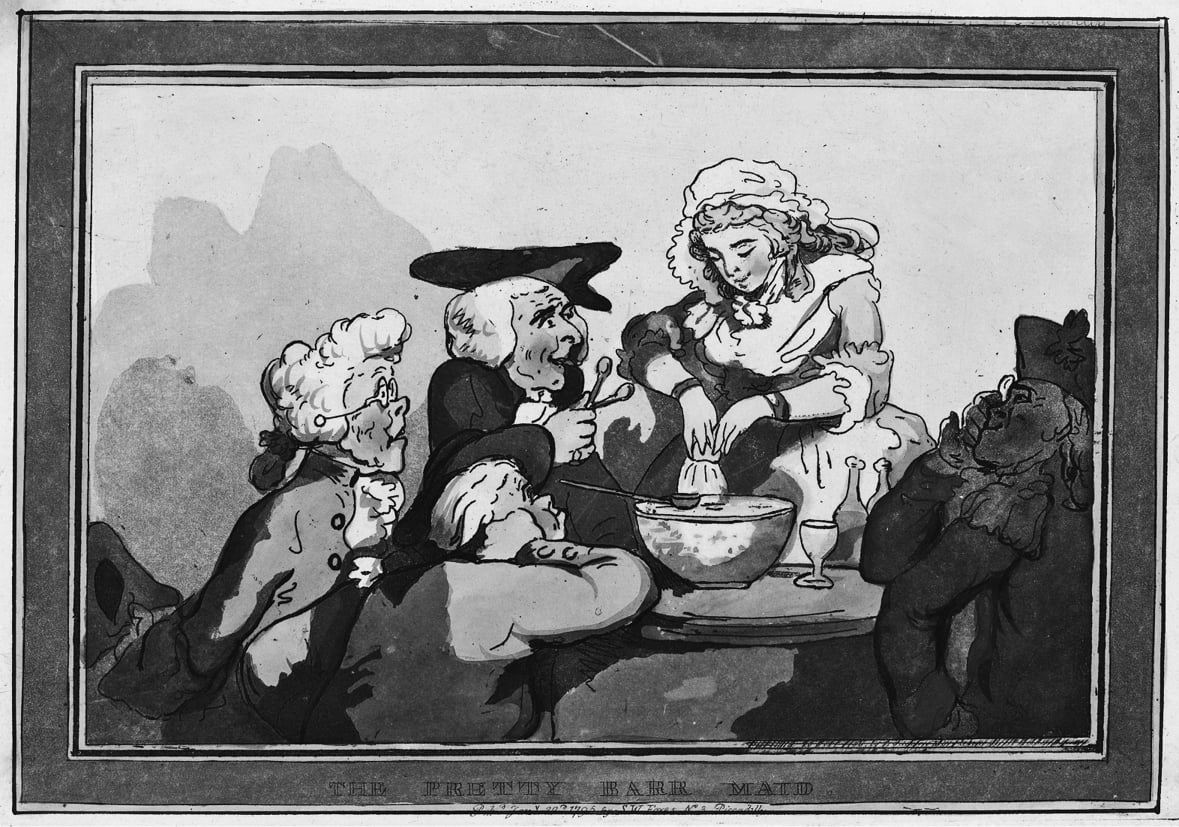

Thomas Rowlandson’s The Pretty Barr Maid, 1795. The barkeeper squeezes lemons while the besotted gent with the black hat holds her sugar tongs at the ready. Source: Wondrich Collection.

Thomas Rowlandson’s The Pretty Barr Maid, 1795. The barkeeper squeezes lemons while the besotted gent with the black hat holds her sugar tongs at the ready. Source: Wondrich Collection.