Ramos, Henry Charles (1856–1928), was born in Vincennes, Indiana, on August 7, 1856, the son of Prussian immigrants. By 1870, the family was settled in New Orleans, where his father was working at the Navy Yard. In 1874, the younger Ramos began working at Eugene Krost’s popular lager beer saloon on Exchange Place, across the street from the Sazerac House. See Sazerac House. In 1876, after a stint at another such establishment, which was operated by Hugo Redwitz on Common Street (it’s unknown if Ramos was working there on Mardi Gras that year, when the bar served an epic seven thousand glasses of beer), he moved to Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Ramos would remain there for more than a decade.

Ramos’s first job in the new city was at the Sumter House, Baton Rouge’s leading saloon and a full-service, American-style bar, where the bartenders had to also be mixologists. Ramos evidently learned more than just the rudiments of the art there. In 1880, when he struck out on his own to open the Capitol Saloon, the local paper observed that “what he doesn’t understand about mixing good drinks ain’t worth knowing.” The Capitol soon took its place among the leading saloons in town. A large, modern establishment, it offered billiards, coin-operated games, and all the popular barroom amusements of the day.

After selling his interest in the Capitol Saloon at the end of 1886, Ramos took over Pat Moran’s Imperial Cabinet saloon at the corner of Carondelet and Gravier streets, in New Orleans’s central business district. That was in May 1887. By 1891, he was being described as “genial and universally-popular” and a man who was “born in Mixerville,” where all the good mixologists come from. By 1895, the New Orleans Times-Democrat was describing the Imperial Cabinet as probably the “one place in New Orleans” best known “among men of the world throughout the United States.”

What made it so was, of course, the Ramos Gin Fizz. A simple Silver Fizz cushioned with cream, rendered mysterious with orange flower water, and shaken until all the ice was incorporated, this sweet, lightly alcoholic drink made Ramos world-famous and very prosperous. See Ramos Gin Fizz and Silver Fizz. By 1899 Ramos’s Fizz was being mentioned in newspapers all around the United States, sometimes under the name “New Orleans Fizz.” The next year, the Kansas City Star dubbed the Imperial Cabinet “the most famous gin fizz saloon in the world.” Any visitor to New Orleans, male or female, made his saloon, one of the few in America considered civilized enough for women to be admitted, one of their first stops.

While Ramos made other drinks besides fizzes, only two or three of them have come down to us—a Creole Cocktail that is essentially a Sazerac, a Taft Cocktail (the same thing in a glass with a sugared rim), and a complex take on the Sherry Flip that was flavored with “squee-gee,” a house mix of liqueurs. But it was the fizz that brought in the customers, in ever-increasing number.

Ramos’ saloon was always busy, but, of course, on Mardi Gras it was almost a frenzy. A crew of bartenders, ranging from eight in 1899 to as many as fifteen ten years later would stand behind the bar, each with one or two “shaker boys”—young black men whose job was to strenuously shake the drinks that the bartenders mixed, for as long as five minutes and more, until all the ice was melted into the drink. The saloon would make some three thousand fizzes a day—so many that Ramos made a second specialty of those flips, which used egg yolks, served egg-yolk omelets on his free-lunch buffet, and still did a thriving business selling the rest of the yolks to bakers. In 1899, Leslie’s Weekly noted that “he has the largest hennery in the country.”

By then, Ramos was a fixture in New Orleans. (In 1903, when the local Times-Picayune ran a picture of him taken from behind and asked its readers to guess who it was, several hundred readers guessed correctly.) Operating what was widely regarded as the most gentlemanly saloon in the city, Ramos tolerated no rowdyism at any time, usually kept the place closed on Sundays, and indeed rarely stayed open past eight on other nights. His saloon was considered so respectable that, as Alderman Sidney Story wrote in 1913, “it is not an unusual sight in the winter months, and when the Carnival is on in New Orleans, to find this palatial resort … packed not only with men but ladies who have just left the fashionable ball-rooms or the French Opera.” It did not hurt that Ramos was active in local politics, club life, and Masonry and served on civic commissions. When Prohibition sentiment began to coalesce in New Orleans, his fellow saloonkeepers deemed him the natural choice to lead the opposition. It helped greatly that, unlike many of his peers, Ramos was abstemious in his personal habits and a good businessman, investing widely in real estate and other businesses. (When, in 1907, a rent increase forced him to move around the corner to Storyville kingpin Thomas Anderson’s Stag Saloon on Gravier Street, he and his partners, his younger brother William and head bartender Paul Alpuente, were soon able to buy the building.)

See also: Schmidt, William; and Thomas, Jeremiah P. “Jerry.”

“A Famous Mixologist.” New Orleans Times-Democrat, September 1, 1895, 28.

“How Late H. C. Ramos Made His World Famous Gin Fizz.” New Orleans Item-Tribune, September 23, 1928.

“The Man Who Remembers His Friends.” Louisiana Review, December 30, 1891, 4.

“People Talked About.” Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly, January 19, 1899, 43.

Ramos, Paul H. Letter, New Orleans Times-Picayune, April 27, 1981, 14.

By: David Wondrich

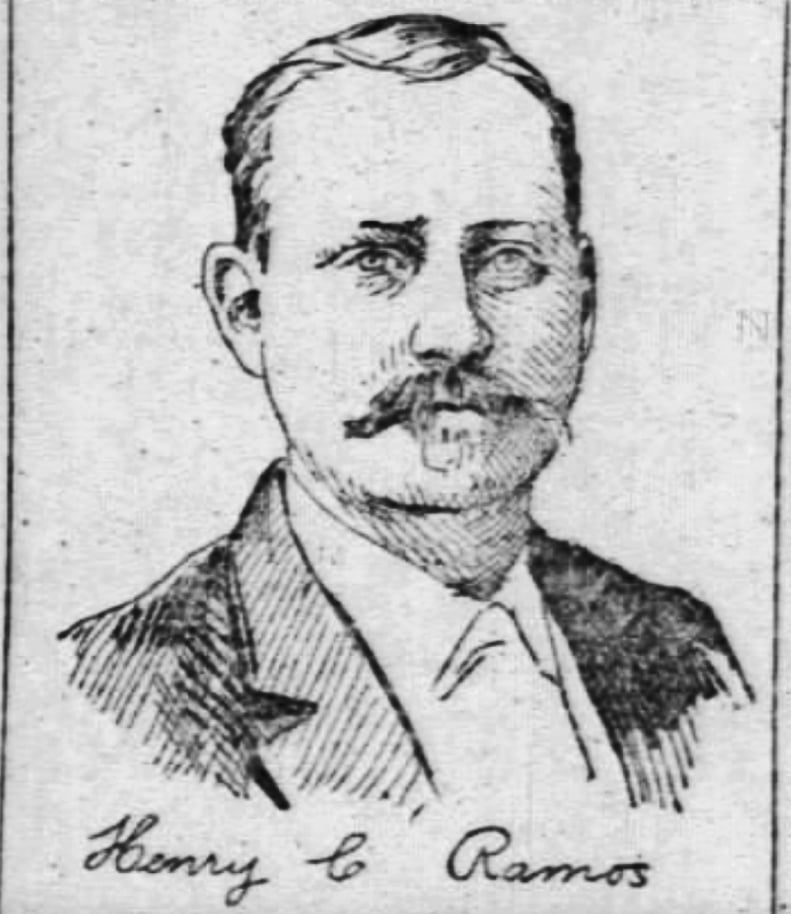

Henry Carl Ramos in 1895, just as his eponymous Gin Fizz was beginning to lift him to fame and fortune.

Wondrich Collection.

Henry Carl Ramos in 1895, just as his eponymous Gin Fizz was beginning to lift him to fame and fortune. Source: Wondrich Collection.

Henry Carl Ramos in 1895, just as his eponymous Gin Fizz was beginning to lift him to fame and fortune. Source: Wondrich Collection.